Main Page: Difference between revisions

→The rocket: adding links to rocket pages |

→News: august: work on blade manufacturing process |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==News== | ==News== | ||

'''''May 21, 2012: ''''' Boeing [http://www.aviationweek.com/Article.aspx?id=/article-xml/AW_05_21_2012_p25-458597.xml has announced] its low cost orbital launch system, based on the WhiteKnightTwo carrier craft and a hypersonic air-breathing first and second stages. | '''''August 2012 update: ''''' A first step in the project realization will be a turbofan's compressor blade manufacturing, in order to validate the manufacturing process suitability and low cost for the turbofan. The first compressor stage prototype has to be designed in this optics. However, that requires having a [[Rocket:First_approximations|first approximation]] of the rocket mass in order to also have an estimation of the aircraft size and mass, from which we can estimate turbofan engine's properties: inlet speed, required thrust, blade length, RPM and so on. Blade manufacturing will mostly rely on a thermocaster that we'll have to design too. | ||

'''''May 21, 2012: ''''' Boeing [http://www.aviationweek.com/Article.aspx?id=/article-xml/AW_05_21_2012_p25-458597.xml has also announced] its low cost orbital launch system, based on the WhiteKnightTwo carrier craft and a hypersonic air-breathing first and second stages. | |||

'''''May 2012 update:''''' Study is still heavily under way in order to validate our [[Turbofan:Alternative_Designs|alternate turbofan mode of operation]]. This is the first thing to validate before the project can enter a real engine design phase of the engine, which will in turn allow the plane to be designed. | '''''May 2012 update:''''' Study is still heavily under way in order to validate our [[Turbofan:Alternative_Designs|alternate turbofan mode of operation]]. This is the first thing to validate before the project can enter a real engine design phase of the engine, which will in turn allow the plane to be designed. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 21: | ||

'''''February 2012 update:''''' Study of aerodynamics is under way. More man power is expected in April. | '''''February 2012 update:''''' Study of aerodynamics is under way. More man power is expected in April. | ||

'''''November 2011 update:''''' Information available on this site is sometimes outdated, and may | '''''November 2011 update:''''' Information available on this site is sometimes outdated, and may be weakly verified or partly false information, since it was done with little knowledge on the topics at the time. A documentation base is being built to provide access to all or a major part of information used to develop the project; the website pages are slowly updated to reflect the actual progress. | ||

==How to escape from Earth?== | ==How to escape from Earth?== | ||

Revision as of 17:00, 14 August 2012

N-Prize and reflections on low-cost access to space

This Web site aims to gather my researches in the field of astronautics, rocketry and other launch technologies that can be used for the N-Prize competition. It is not an official Web site for the N-Prize. The official Web site is here: http://www.n-prize.com/. The goal of this competition is roughly to reproduce the great achievement of the Sputnik in 1957, but for a 20g satellite and with less than £1000. However, the Web site and its associated research will not stop after the contest is over, this is more a long term (should I say lifetime?) project. It is hosted by the Open Technology And Science Knowledge Initiative (OTASKI).

I'm not part of a team for the N-Prize, nor did I register one, because I don't really have the expertise and resources to actually build something in time before the deadline of the contest in september 2013. Anyway, if you find this project interesting, you can join and participate! Maybe if we are enough to work on the project, it is possible to make it. It is also possible to provide a part of the challenge and join together with another team providing the other part. Other teams have for example been developing satellites, rocket engines, and so on.

What is the LCAS project?

LCAS, standing for low-cost access to space, aims to provide a low cost orbital launch system for small size satellites, probably with a mass lower than 1kg. Research has led us to consider using an aircraft for rocket launches, the body of the plane being the rocket itself. The rocket, as in any other orbital launch system, would make it to orbit and thus could embed a minimum of science, making optional the use of a real satellite as payload. Since the main constraint is to have low costs, we'll have to design and build the carrier plane first, including its turbofan engines, which is probably the hardest part of the whole project, and as far as we know has never been done by amateurs.

We thus currently focus on the turbofan research and design, on which depends everything else. We may then consider helping other N-Prize teams if this is done in time, or other similar projects outside the contest, by providing them those engines and help with aircraft design and rocket integration. Some other parts of the aircraft/rocket are also being studied, for example the software control and the low-cost sensors that can be used to render the aircraft autonomous at first, then make the rocket go into space and reach orbit.

News

August 2012 update: A first step in the project realization will be a turbofan's compressor blade manufacturing, in order to validate the manufacturing process suitability and low cost for the turbofan. The first compressor stage prototype has to be designed in this optics. However, that requires having a first approximation of the rocket mass in order to also have an estimation of the aircraft size and mass, from which we can estimate turbofan engine's properties: inlet speed, required thrust, blade length, RPM and so on. Blade manufacturing will mostly rely on a thermocaster that we'll have to design too.

May 21, 2012: Boeing has also announced its low cost orbital launch system, based on the WhiteKnightTwo carrier craft and a hypersonic air-breathing first and second stages.

May 2012 update: Study is still heavily under way in order to validate our alternate turbofan mode of operation. This is the first thing to validate before the project can enter a real engine design phase of the engine, which will in turn allow the plane to be designed.

February 2012 update: Study of aerodynamics is under way. More man power is expected in April.

November 2011 update: Information available on this site is sometimes outdated, and may be weakly verified or partly false information, since it was done with little knowledge on the topics at the time. A documentation base is being built to provide access to all or a major part of information used to develop the project; the website pages are slowly updated to reflect the actual progress.

How to escape from Earth?

Rockets have been used for 50 years to escape the gravity of earth. They are good for three things: create an important thrust, go fast, and burn a lot of ergols. Indeed, the efficiency of a propulsion engine is measured with a specific impulse (I_sp), and for rocket engines, it is quite low. However, they are the only engines that provide the sufficient thrust to climb up with large speeds and to tear of Earth's gravity.

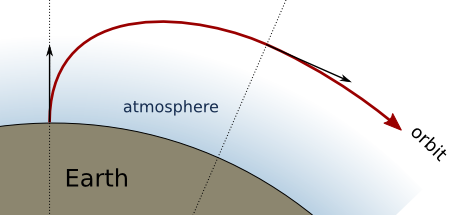

Besides altitude, speed is the most important factor when trying to put an object into orbit. Without it, satellites would fall back down on Earth, even if you climb up at 200 miles. Once again, rocket engines, with their high thrust power can achieve sufficient speed before falling back on Earth.

Rocket trajectories generally tend to form a square angle, with the beginning of the flight being orthogonal to Earth and the final direction being parallel to Earth's surface. The reason is that since they achieve ultra-sonic speeds very quickly, the air pressure on their body (mainly the fairing) becomes quite important. It is more efficient to first escape the low atmosphere, with its 85% of its whole mass below 11km altitude, and then change trajectory to gain the horizontal speed needed for orbital injection without being slowed down by atmospheric friction.

That particular point of the cost of escaping the atmosphere made me thought about using an aircraft to launch a rocket from the upper atmosphere, reducing considerably the air pressure, the drag, and improving trajectory and efficiency. Moreover, the specific impulse of a turbofan is around ten times greater than the Isp of a rocket engine, since it uses oxygen from the atmosphere to burn its fuel, and not some embedded oxidizer. The fact that it uses a turbine design also has a great impact on the improvement of efficiency. For the N-Prize, the cost of the aircraft could be deducted from the overall price since it would be reused.

I started searching and I found out that Orbital already has developped an air-to-orbit launch vehicle, called the Pegasus. It is able to push onto Low Earth Orbit a payload up to 1,000 lbs (450 kg), and it is launched from a full-sized airplane. My goal is thus to study the feasibility of something similar, at very low price, even for the aircraft. A rocket would still be used for air-to-orbit link because nothing else is able to achieve a speed around 9 km/s before falling back on Earth. Some specific technologies can be used to improve efficiency, we'll see them below in the rocket section.

Several teams are working on using Helium or Hydrogen balloons (rockoons) to get to the high atmosphere, around 35km and then launch a rocket. It is a nice solution too, and maybe less expensive in the overall, but balloons are not reusable, suffer from imprecise trajectory due to winds, and provide no initial speed. This latter point is questionable, since the initial speed of such a plane would still be quite low.

Single stage to orbit (SSTO) are also a promising research field for low cost orbiting. This one (SpaceX guys), here captured at SpaceUP, doesn't even allow attitude control out of atmosphere to avoid expensive guidance actuators. The main idea of SSTO is that the launch system (rocket) is the payload. It does not aim to insert a smaller satellite into orbit.

The aircraft

Some aircrafts have been exploring the high atmosphere, around 30km high. Contrary to what one would assume, high flight speeds are not needed, if the weight is kept low. The Helios for example, autonomous solar powered aircraft, flights at this altitude at 20km/h. John Powell [1] is also researching on high altitude propellers and plans to make it to space using a high altitude base for payload transfer to a bigger plane. He describes it well in this video interview. The U-2 is a manned reconnaissance aircraft flying at 21km altitude, but cruising at relatively high speeds (690km/h). Those planes are designed with a very long wingspan, and low weight, similar to gliders.

Another kind of design it the fighter jet, for example the MiG-25 which also was an altitude (amongst other) record breaker. It had two powerful turbojet engines with afterburner, allowing him to reach a service altitude of 20km and a maximum altitude of more than 37km. It however required a thrust (200kN) nearly equivalent to the empty weight of the plane (20,000kg) and large amounts of fuel to climb this high.

These concerns of how high altitude is reached - mainly through high engine power or high lift at subsonic flight - is discussed on the page dedicated to high altitude flight.

Nevertheless, we would benefit from speed of the aircraft, speed that wouldn't be needed by the rocket to reach. It is a low speed compared to orbital speed though. Supersonic launch speed would be nice, but very hard to achieve. Currently, only subsonic speed is considered in the project.

Can electricity energy be considered for that kind of mission? If not, what fuel should be used, kerosene, alcohol, E85?

Anyway, a major issue with the aircraft is: how to build a £100 turbofan? Small turbofan engines exist, but are made for or by the military, so very expensive and their use is restricted to missiles or UAVs.

Staging and recovery

Separation from the rocket is a big concern. If wings and tail are directly mounted on the rocket body and jettisoned, they would not need some guidance or attitude control electronics, just a basic parachute system. If the wings are able to fly without the rocket, two guidance systems are needed: one for the rocket and one to get back the aircraft in one piece for future launches. Keeping the N-Prize in mind, the aircraft part of the space launch system should be reusable, so that it doesn't count in the £1000 limit. In that case, it has to be recovered in good condition, either using a chute and a GPS tracker, or a complicated autonomous return-to-runway and landing system.

Guidance

A satellite navigation system can probably be used in the plane for position tracking. Other sensors should be shared with the rocket's embedded computer, if choices made for staging and recovery allow it.

Sun position can be a very good and easy indicator of attitude, as well as earth curve recognition. Video camera is likely to be the main sensor, since it can provide lots of information for very low cost (but for high processing power).

See the page on the embedded computer.

The rocket

Some concerns are emphasized in this section, some choices are made too. A list of concerns and how they are handled by existing engine designs can be found on the rocket engines page. For the first approximations of the capabilities and properties of our rocket and rocket engine, for example the minimum weight required to achieve orbit, see the first approximations page.

Fuel

Propellants represent the most important part of the weight of what we have to launch. It should thus be chosen carefully regarding to its cost.

Alcohol has been used in the early ages of rocketry, in the German V-2 for examples. It has the advantages to be cheap, and burns quite well. It is not pure, generally used between 75 an 90 percent of volume ratio with water for the rest. The loss of weight due to that water is often a good thing because it burns producing so much heat that the water can keep the engine cool enough to survive. Rocket-grade kerosene (RP-1) has been introduced later to replace alcohol, providing a better volume efficiency.

To my eyes, alcohol seems to be a very good low cost solution. RP-1 is still used nowadays, and is only 20% more efficient than alcohol with a liquid oxygen (LOX) oxidizer. The next question is thus: should we use some pure alcohol, alcohol/water blend or alcohol/something else blend?

I believe that E85, a 85 percent alcohol and 15 percent gasoline fuel recently put on the automotive fuel market, makes a promising rocket fuel. Its efficiency should be slightly better than alcohol, still being very cheap, around £0.5 a liter.

Alcohol has good (regenerative) cooling properties but the non-refined 15% hydrocarbon in it may prevent to use it as a coolant. E85 has a different air-fuel ratio than gasoline, requiring less oxygen (or more fuel) to burn, which can be a good thing for us since a cheap LOX tank may be heavy, so the smaller the better.

Oxidizer

Liquid Oxygen (LOX) is the obvious/best choice for high Isp. However, it has lots of drawbacks because of the need for cryogenics storage, cautious manipulation, and engine design, that make it quite expensive and much complicated. See the cryogenic engineering book.

Other leads should then be explored, like Nitrous oxide.

Hydrogen peroxide would even be better, since it's more dense, but it seems complicated and expensive to have it manufactured at a high concentration.

Engine

Aerospike engines may be considered, although they are more efficient than bell shaped nozzles at low altitudes and that we want to launch from high altitude. See web page on nozzle design.

The pump is also a major concern, especially for cost and chamber pressure capability. Xcor has created in 2003 a piston pump for LOX, which is now used on a 1,500 lb-thrust LOX/kerosene engine.

More details on the rocket engines page.

Trajectory

The trajectory has to be precise enough to get a launch authorization for a specific orbit, and in a more practical way, to have orbital parameters matching the mission requirements. Trajectory interpolation is closely tied to attitude control. I believe that mere cameras can be used on the rocket to determine position of the sun and the Earth's horizon. That will have to be validated, but even if it only allows launches at specific times with clear skies, it can be acceptable for a low-cost launch system. Accelerometers, digital gyroscopes and a compass are really cheap nowadays and can be used for attitude monitoring too. They will likely be used in the fast attitude control loop and to refine the attitude calculated by the camera system.

Anyway, if sensors are available, actuators are different story. Two ways of changing attitude of a rocket are generally used, as fins have no impact in the vacuum of space: 1) the rocket engine has to be directionally controllable (generally using hydraulic actuators, or more in a more innovative way, using electromagnetic actuators like Vega's P80), or 2) control jets (also known as the RCS) must be used to control the attitude of the rocket, as partially does SpaceX with the Merlin engine. Both cases imply complications on the rocket's and engine hardware, but are mandatory in our case. This is one of the big differences between sub-orbital and orbital space flight.

The satellite

Lots of strategies for the tracking of the satellite have been exposed: flashing device, radioactive, EM emitting, mirrors... The ground segment will have to be developed from scratch since I don't think anybody would mind tracking 20g 100miles away.