Build a cheap turbofan: Difference between revisions

→How to build a cheap (~ $150) turbofan?: rewriting parts |

→Design versus manufacturing: blades... |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==Design versus manufacturing== | ==Design versus manufacturing== | ||

Design configurations and properties taken into concern on real engines tend to increase efficiency, i.e. higher thrusts for lower fuel consumption, but also try to reduce the exhaust noise. Cost is of course a concern, and an efficiency by itself, but not a constraint | Design configurations and properties taken into concern on real engines tend to increase efficiency, i.e. higher thrusts for lower fuel consumption, but also try to reduce the exhaust noise. Cost is of course a concern, and an efficiency by itself, but maybe not a hard-constraint as it is for us. Safety of operation is their primary concern, whereas cost and ease of maintenance are our primary concerns -- and maintenance will be an important part of the job if the quality goes down because of the price. | ||

===Shaped core or shaped shaft?=== | ===Shaped core or shaped shaft?=== | ||

An important optimization to reduce cost and complexity of manufacturing | An important optimization to reduce cost and complexity of manufacturing could be to have a simpler design of the parts creating the gas volume of the engine's core, i.e. the rotor(s) and the stator. In the above schema, we see that the shaft is straight and that the core envelope is curved suit required volume on each stage, although in real life, both are curved. If we take the required volumes on each stage and that we fix the core's envelope shape to a cylinder, the shaft will have a bumped profile (small-large-small diameter). This is much less expensive to produce, with a simple [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lathe lathe] ([http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turning turning]). Earlier engines, like the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J79 J79], have a cylindrical envelope. A curved envelope is complicated to build, requiring welding, pressing, stage bolting, the same techniques used in stator-construction in modern engines. | ||

Real-world engines don't have a massive turned shaft because of the weight. They consist of plates for each compressor and turbine stage, that are linked together to the next stage using a cylindrical bolted joint. So basically, the shaft has no core, | Real-world engines don't have a massive turned shaft because of the weight. They consist of plates for each compressor and turbine stage, that are linked together to the next stage using a cylindrical bolted joint. So basically, the shaft has no core, it's hollow, except for the plates on each stage. Our small engine design allows us to have a more simple design, since having a massively-turned shaft won't change much on its final mass. Moreover, we may think about a turbine-stage mechanism embedded in the stator to try to cool it, which would make it hollow. The main issue is now how to properly fix the blades to it and how to balance it/them? | ||

[[Image:500px-Turbofan_craftedshaft.svg.png]] | [[Image:500px-Turbofan_craftedshaft.svg.png]] | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Compressor and turbine blades=== | ===Compressor and turbine blades=== | ||

The most complicated | The most complicated parts to build in a turbofan or turbojet engine are the turbine and compression blades. The high-pressure turbine specially have to face very high temperature and pressure. On real engines, they are made of nickel-based [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superalloys superalloys]. It's the inability of blades to withstand heat and work that limit the power of the engine, because the gas generator (combustion) and the compressor can provide more power to the turbine. | ||

The compressor is not only made of blades on the rotor, but also blades on the stator. They prevent a rotating air flow to form inside the engine, driven by the action of | The compressor is not only made of blades on the rotor, but also blades on the stator. They prevent a rotating air flow to form inside the engine, which would decrease the enthalpy of the gas (its internal energy), driven by the action of rotor blades. Stator blades redirect the airflow on the next compression stage in the more appropriate and efficient direction. | ||

Highest efficiency is reached in turbofans when gaps are reduced between blades and the stator, | Highest efficiency is reached in turbofans when gaps are reduced between rotor blades and the stator, as well as between the stator blades and the rotor. As always, good efficiency means good high precision and higher cost. Anyway, the precision of blades will have to be very good if we don't want it to dislocate when it reaches the high rotations-per-minute achieved by such engines. | ||

Blade geometric design by itself can reveal complicated. The first engine(s) had flat blades. At the time, the efficiency of the engine was so terrible that it was believed that turbojets would never beat reciprocating engines. Then, in 1922, XXX proved that it blades were designed as airfoils, the engine would behave way better, and would even be efficient enough to be built. Airfoils for blade design allow the compressor stages to better increase the velocity, since they provide a reducing area for the air to pass through (= a compressor), converter to pressure by stator blades. For turbine blades, it's the opposite, they provide a gas expander by increasing the area through which hot gases flow. | |||

==Design considerations== | ==Design considerations== | ||

Revision as of 20:38, 2 May 2011

This page gathers general information on turbofans. Our proposed design is scattered in several pages, with an index at the bottom of this page.

How to build a cheap (~ $150) turbofan?

Turbofans are the most efficient engine design for subsonic speeds cruising. They are more powerful and way lighter than reciprocating engines, fly at higher speeds than turbopropellers, and are less fuel-greedy than supersonic-enabled turbojets. They are however very difficult to manufacture as well as very expensive. On this page, we will explore how costs can be reduced while still having a reasonable efficiency, which is our primary concern here.

General principles

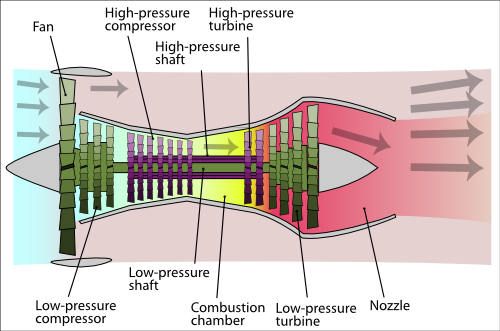

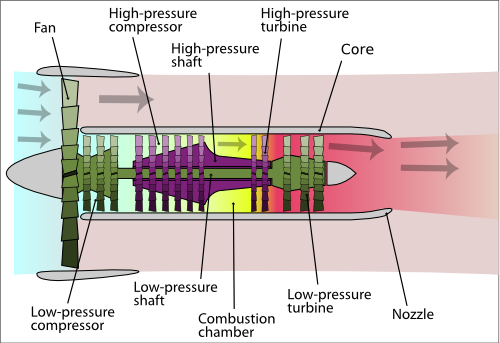

Lots of information are available on Wikipedia's page. General principle is that there is a combustion that feeds a turbine, which drives the fan and the compression stage feeding the combustion. The fan provides thrust from creating a massive air flow, and the turbine creates thrust by evacuating a hotter but less important air flow. As air is compressed from the intake, more air becomes available for combustion, and thus create more work on the turbine, and more intake.

Some design properties and configurations have to be properly calculated depending on the use of the engine, mainly for the intended aircraft speed:

- The Bypass ratio (BPR) is a ratio between the mass flow rate of air drawn in by the fan but bypassing the engine core to the mass flow rate passing through the engine core. A BPR = 0 would be a turbojet engine. The higher BPR, the more efficient the engine, but also the slower exhaust speed.

- The number of spools: modern engines embed a second and sometimes a third concentric shaft for high pressure operations. The low pressure shaft, the innermost has the fan mounted on. One stage engines exist and are less complicated and expensive to build, but are also less efficient. Indeed, higher rotation speeds in the internal spools allow to provide a more efficient compression. A gearbox may be needed to drive the fan if the shaft has a too important rotation speed in the case of a single-spooled turbofan. Multi-spooled engines prevent this issue, by keeping the low-pressure stages at relatively low speeds, suited for the fan.

- The compression ratio is the ratio of the pressure of intake air on compressor discharge air. It is closely determined by the number of stages in the compressor and their efficiency. More compression means more air to blend with fuel and to cool the engine, and even more pressure at output, increasing the speed and mass of output gas, and thus the work that can be extracted by the turbines and overall engine efficiency.

Turbojet/turbofan engine simulation software from NASA: EngineSim

A must-read book by Klaus Hünecke: Jet engines: fundamentals of theory, design, and operation.

Video documentaries from a turbine renovator in Canada, probably the best resource on the Web for seing what's inside real engines: on youtube. Thanks AgentJayZ!

Design versus manufacturing

Design configurations and properties taken into concern on real engines tend to increase efficiency, i.e. higher thrusts for lower fuel consumption, but also try to reduce the exhaust noise. Cost is of course a concern, and an efficiency by itself, but maybe not a hard-constraint as it is for us. Safety of operation is their primary concern, whereas cost and ease of maintenance are our primary concerns -- and maintenance will be an important part of the job if the quality goes down because of the price.

Shaped core or shaped shaft?

An important optimization to reduce cost and complexity of manufacturing could be to have a simpler design of the parts creating the gas volume of the engine's core, i.e. the rotor(s) and the stator. In the above schema, we see that the shaft is straight and that the core envelope is curved suit required volume on each stage, although in real life, both are curved. If we take the required volumes on each stage and that we fix the core's envelope shape to a cylinder, the shaft will have a bumped profile (small-large-small diameter). This is much less expensive to produce, with a simple lathe (turning). Earlier engines, like the J79, have a cylindrical envelope. A curved envelope is complicated to build, requiring welding, pressing, stage bolting, the same techniques used in stator-construction in modern engines.

Real-world engines don't have a massive turned shaft because of the weight. They consist of plates for each compressor and turbine stage, that are linked together to the next stage using a cylindrical bolted joint. So basically, the shaft has no core, it's hollow, except for the plates on each stage. Our small engine design allows us to have a more simple design, since having a massively-turned shaft won't change much on its final mass. Moreover, we may think about a turbine-stage mechanism embedded in the stator to try to cool it, which would make it hollow. The main issue is now how to properly fix the blades to it and how to balance it/them?

Compressor and turbine blades

The most complicated parts to build in a turbofan or turbojet engine are the turbine and compression blades. The high-pressure turbine specially have to face very high temperature and pressure. On real engines, they are made of nickel-based superalloys. It's the inability of blades to withstand heat and work that limit the power of the engine, because the gas generator (combustion) and the compressor can provide more power to the turbine.

The compressor is not only made of blades on the rotor, but also blades on the stator. They prevent a rotating air flow to form inside the engine, which would decrease the enthalpy of the gas (its internal energy), driven by the action of rotor blades. Stator blades redirect the airflow on the next compression stage in the more appropriate and efficient direction.

Highest efficiency is reached in turbofans when gaps are reduced between rotor blades and the stator, as well as between the stator blades and the rotor. As always, good efficiency means good high precision and higher cost. Anyway, the precision of blades will have to be very good if we don't want it to dislocate when it reaches the high rotations-per-minute achieved by such engines.

Blade geometric design by itself can reveal complicated. The first engine(s) had flat blades. At the time, the efficiency of the engine was so terrible that it was believed that turbojets would never beat reciprocating engines. Then, in 1922, XXX proved that it blades were designed as airfoils, the engine would behave way better, and would even be efficient enough to be built. Airfoils for blade design allow the compressor stages to better increase the velocity, since they provide a reducing area for the air to pass through (= a compressor), converter to pressure by stator blades. For turbine blades, it's the opposite, they provide a gas expander by increasing the area through which hot gases flow.

Design considerations

Temperature control

Cooling might be needed if low cost metals are used. Expected combustion chamber temperature is around 2000°C for hydrocarbon or alcohol fuels. Iron melting point is around 1500°C. Cooling may be done by injecting low temperature air in the hot flow, or use film cooling in the combustion chamber.

Startup

Startup can be done at ground manually (with compressed air for example). Igniter has to be integrated to the engine, possibly a self-maintaining igniter like a thread of tungsten or something similar. The combustion should be self-igniting and self-maintaining, but if pumps or throttling lead to a discontinuous flow of fuel, the igniter will have to be available during the flight.

Providing power to the aircraft

APUs and turbine engines provide power to aircrafts, either in an electric, hydraulic or pneumatic form. It would be nice to have an electrical power generator in our turbofan engines, because batteries are heavy. This is generally provided by the same mechanism than startup, used reversely, like an electric engine/alternator.

Sensors

Engine must be designed with sensors, at least to determine if the engine is running properly or if it's under failure. That can be done with a rotation sensor, measuring the magnetic field disturbances created by the blades or the rotor, possibly using a magnet (not recommended due to the manufacturing process and temperatures it may face). Engine temperature should be recorded too. Pressure at different stages would be very useful for engine development, then for behavior indications when running at high altitude, but may be too heavy or expensive to put on the real engine.

Fixing blades to rotor

In real engines, blades are fixed like this, with a shape that allow them to be mounted and remove axially but not orthogonally. The main problem appearing with this kind of mount is related to the size of the engines we need. As the diameter of the fan shaft gets smaller, the available space for the blade inserts gets smaller, and require a higher precision for their manufacturing. The strength applying to the fixation is luckily reduced due to the small weight of the blades, and maybe a simple design similar to the one above, but based on only one squared holder is enough.

Fixing blades to stator

To be studied.

External hardware

Fuel tanks in the wings, fuel pumps, fuel lines, and engine mounting will have to be considered if turbofans are used. Sensors will require input ports on the computer, and pump driving (= engine control) will require at least one output port for each engine on the computer.

Stator/rotor bearing

Two kinds of bearings are used in turbines.

- Ball bearing: stator and rotor are joint using a ball bearing constantly bathed in oil to survive to high speeds.

- Fluid bearing: pressurized oil prevents parts from touching, due to hydrostatic. Longer life and no maintenance.

Carbon lip seals prevent the oil from escaping to other parts of the engine.

Our Design propositions

From the different concerns expressed above, we propose a design for a low-cost turbofan. We also consider and propose innovative alternative turbofan designs. Several pages have been created in the Turbofan category to explain each subsystem and parts manufacturability:

- Compressor: A three stage compressor, with a design allowing easy manufacturing.

- Blades: How to design an cheaply manufacture compressor, turbine and fan blades.